Astrophotography has been around for almost as long as photography itself.

But until relatively recently, getting good results in astrophotography required access to some very serious photographic kit.

Yet rapid advances in imaging technology mean that capturing the night sky in stunning detail has never been as achievable as it is today. And what better way to do so than with Nikon’s top-end range of Mirrorless cameras; the Nikon Z series.

However, although Nikon’s Z system offers a rapidly expanding range of superb quality glass, choosing the right Nikon Z lenses for astrophotography is not as straightforward as you might first imagine.

In fact, it turns out that the best way of shooting astrophotography with Nikon’s Mirrorless models may not be using any of the native Nikkor S lenses at all.

Read on to find out why most Nikon Z lenses won’t cut it for astrophotography, and learn which third-party lenses make the grade instead.

In this article, I rank the best lens options for shooting astrophotography on Nikon Z6, Z7, and Z50 cameras.

But before making your own choice from among those on our list, be sure to read our buyer’s guide below explaining what to look for in an astrophotography lens.

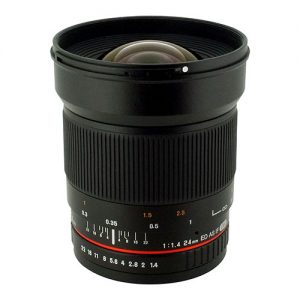

The Rokinon 24mm f/1.4 is a fast, well-priced, and solidly-built wide angle lens, offering a field of view that is ideal for astrophotography on full frame cameras.

However, APS-C camera owners could also just about get away with using Rokinon 24mm for shooting the night sky too, where it will provide a focal length equivalent to 38mm on full frame.

When it comes to astrophotography, the main draw of the Rokinon 24mm is its excellent optics combined with true manual focusing capabilities.

Pros

- Fast maximum aperture

- True manual focus

- Very sharp

- Almost no coma effect or chromatic aberration

- Affordably priced

Cons

- No image stabilization

Central sharpness is very impressive even wide open, and while there’s a degree of softness towards the corners, performance is nonetheless very good even here.

Performance in this department only improves as the diaphragm is stopped down to f/2.8, where overall sharpness and contrast are truly amazing from edge to edge.

What’s more, this lens exhibits only minimal chromatic aberration, and even more importantly there’s little or no coma, especially when used at f/2 and beyond.

The only noticeable defect is some barrel distortion, but this is easily fixed at the editing stage.

Keep in mind that the Rokinon/Samyang 24mm f/1.4 is manual focus only; an advantage for shooting the night skies, but less appropriate for many other genres of photography.

Thankfully though, the focus ring provides smooth and precise action and the lens also features a physical aperture ring, making it a pleasure to use.

Although there is no image stabilization, as an astrophotographer you will in any case be using this lens on a tripod nearly all the time.

Consequently this omission will only be of real concern to you if you also plan on using it to shoot other genres of photography.

Note that this lens is superior to the Samyang 14mm f/2.8, and even the 14mm f/2.4 (below); both of which are less sharp and reportedly suffer from fairly frequent quality control issues.

So if you’ve been discouraged by bad experiences with, or reviews of, either of those two lenses, don’t let them put you off the 24mm F/1.4.

Of course, 24mm is a longer focal length, so those seeking a wider field of view will either need to sacrifice image quality or spend a little extra money on one of the wider options we look at below.

As sharpness is of the utmost importance for night sky photography, and primes generally perform better in this department, zooms are rarely the serious astrophotographer’s first choice of weapon.

However, if an ultra-wide-angle zoom is a “must” as far as you’re concerned, they don’t come much sharper and more coma-free than this one; it’s one of the best ultra-wide zooms currently available, outdoing even many prime lenses (for example, the Sigma ART 14mm below) when it comes to coma performance.

Anyone familiar with the first iteration of the Tamron 15-30mm f/2.8 will know that it was a very sharp lens at the center of the image.

The G2 improves upon this already excellent performance, spreading the sharpness right up into the corners.

And although fast maximum aperture wide-angle lenses tend to suffer from chronic vignetting, there’s very little of that detectable here.

Pros

- Very sharp

- Very little coma

- Weather sealed

- Image stabilization

- Real manual focus and AF

Cons

- Maximum aperture slower than on comparable prime lenses

True, if you ever point the lens directly at a brick wall you’ll be sure to notice some quite heavy barrel distortion.

But let’s just say that this is not a major concern for those who only photograph the sky.

As ever though, distortion of this kind is a cinch to fix with software anyway.

Boasting a sturdy metal barrel, and containing 18 glass elements, the Rokinon 14mm f/2.4 is a fairly weighty, but nonetheless compact, ultra-wide prime.

The lens is manual focus only, but handles very nicely via a smooth and well-dampened rubber focus ring, making it well suited to astrophotography.

Images produced using the 14mm f/2.4 are supremely sharp from center to edge, even wide open.

Pros

- Extremely sharp even at widest aperture

- Almost no coma

- Minimal chromatic aberrations

Cons

- More costly than many other Samyang/Rokinon lenses

- Not weather-sealed

Indeed it’s undoubtedly one of the sharpest lenses in its category. Additionally there’s almost no chromatic aberration, and in terms of coma the performance is nothing less than spectacular; thus sealing the Rokinon 14mm f/2.4’s credentials as an outstanding lens for astrophotography.

True, there’s noticeable barrel distortion and vignetting when used at wider apertures.

But this is unsurprising in a lens of this focal length. In any case, it can easily be corrected in post-production.

Do not confuse this lens with the Rokinon 14mm f/2.8, which suffers from much greater quality control problems and is in any case just generally an inferior lens.

However, reflecting its pro-level specs, the 14mm f/2.4 costs considerably more than many other Rokinon primes.

First the good news: Nikon’s newly released 20mm f/1.8 S prime for the Z-mount system is an amazingly good lens optically.

Indeed, it’s a lot sharper than Nikon’s F mount version of this lens, particularly in the corners (although as Z-mount lenses generally tend to perform better than their F-mount counterparts when used wide open, this is not entirely surprising).

Pros

- Very sharp

- Minimal comatic and chromatic aberration

Cons

- Focus-by-wire

- No image stabilization

- Expensive

What’s more, as with all the Nikon Z lenses, the 20mm f/1.8 S is almost entirely free from comatic aberration, thus upping its astrophotography credentials

The bad news, however – at least as far as astrophotographers are concerned – is that manual focus is not the 20mm S’s strong point.

Indeed, nearly all the Z-mount lenses perform badly in this department.

To be clear, autofocus performance is excellent. But for astrophotography, manual operation is generally more advisable.

And with one or two exceptions, all the Nikon S lenses employ the focus-by-wire system; i.e. electronically simulated manual focus.

And with no infinity stops, your only option is to use autofocus or live view mode.

Not at all good for making minuscule adjustments.

You can certainly use this lens for astrophotography, and when you do manage to set focus correctly the results will likely be optically very impressive.

But there are less frustrating (and indeed cheaper) ways of achieving the same ends. This is a shame though, as its undeniably a great lens, and comes at an ideal focal length for shooting trail-free star-scapes.

Lenses in Sigma’s ART series have consistently offered great optics at pretty good prices.

While that remains true with the Sigma 40mm f/1.4, its hardly what you would call a “cheap” lens either; approaching as it does the cost of one of Nikon’s native models.

Pros

- Sharp edge-to-edge

- Good contrast

- Fast maximum aperture

- Minimal chromatic aberration

- Acceptable corner coma performance

- Weather-sealed

Cons

- Big compared to other 40mm lenses

Still, the optics are also on a par with Nikon’s offerings.

And the fact that it comes with genuine manual focus ( rather than feigned variety offered by most of Nikon’s S series glass) will seal the deal for most astrophotographers.

The lens is well built and fully weather sealed. Perhaps more importantly, though, it is crystal sharp in the center, and not far behind at the corners – even at f/1.4.

Indeed, the 40mm f/1.4 is undoubtedly one of Sigma’s sharpest prime lenses.

What’s more, unlike many of the wider focal length models we look at here, barrel distortion is virtually undetectable.

Coma, too, is kept well under control.

Beyond great optics though, one of the primary selling points of this lens for astrophotography is that while the Sigma 40mm comes with highly capable autofocus capabilities, it also features genuine, mechanical, manual focus.

A great improvement over the widely-detested focus-by-wire system used in many modern lenses – including most of Nikon’s Z-mount offerings.

Of course, at 40mm the Sigma is rather long for an astrophotography lens.

However, so many photographers shoot the Milky Way in the same highly formulaic manner, with results that are largely indistinguishable one from the other.

So an opportunity to move away from the predictable point of view provided by an ultra-wide-angle lens will likely appeal to more creative and adventurous night sky photographers.

Even if to do so does present certain technical challenges (see the Focal Length section below for a full explanation of what those challenges are).

With a very fast maximum aperture of f/1.4, though, the ART 40mm goes some way towards overcoming these issues.

The Sigma ART 14mm f/1.8 is a super sharp ultra-wide-angle prime lens that, while not entirely coma-free, nonetheless performs excellently on this front.

Faster and wider than the Tamron 15-30mm (above), it displays minimal flare, distortion, and vignetting, and remains sharp even at its widest aperture setting.

Pros

- Sharp even wide open

- Only minor comatic aberration

- Fast maximum aperture

- Ultra-wide field of view

- Image stabilization

Cons

- Very big and heavy

- Relatively expensive

- No image stabilization

On the downside, the Sigma 14mm is exceptionally big and heavy within its class.

On top of which it lacks image stabilization (but you’re not going to be shooting the night sky handheld anyway, right?).

What’s more, it’s also one of Sigma’s most expensive lenses.

Taken individually on their own, none of the above complaints are likely to be total deal-breakers.

But stacked up and viewed in comparison with options such as the Samyang/Rokinon 14mm f/2.4 (above), they might be enough to swing the pendulum away from the Sigma 14mm.

Just remember, though, that the Samyang/Rokinon 14mm lacks autofocus, so if you also plan on shooting anything else beyond astrophotography this could easily push the balance back in Sigma’s direction once again.

Buying Guide For Nikon Z Astrophotographers

Astrophotography is a unique and rather specific genre of photography.

This means that some of the rules that apply when selecting a lens for other types of photography have little relevance here.

Meanwhile certain aspects of lens design and construction that are of only minor importance in other areas of photography become fundamental when photographing the night sky.

In this section we break down the main technical points you will want to consider when choosing a Nikon Z lens for astrophotography.

Maximum Aperture

When it comes to lenses for landscape photography, achieving a deep depth of field will be most photographer’s main priority.

As a result, for landscape photographers fast maximum aperture is rarely a selling point.

But skyscapes are another matter entirely; here a lens’s light-gathering abilities count like nothing else.

In any case, the long exposure times necessary to correctly expose a nighttime scene at a small aperture such as f/16 just aren’t practical for astrophotographers, who are effectively photographing stationary objects (stars) while they themselves are standing on a giant rotating ball (planet Earth).

The earth’s rotation isn’t detectable to the naked eye, but if the exposure time is too long, it will clearly show up in a photograph of the night sky as blurred stars.

Using a faster ISO will of course permit shorter shutter speeds, but this also comes with increased digital noise. Not a good solution.

The best tactic for astrophotography, then, is to use a fast lens, so as to keep exposure times to a minimum and ISOs low.

How long an exposure you can get away with before you start to see star trails (motion blur) depends on a number of different factors, such as sensor size, lens focal length (see below), and even the direction in which you point your camera.

Thankfully there’s a handy rule for determining which shutter speed you should use in any given situation.

To recap then, one of the most important attributes of a good astrophotography lens is a fast maximum aperture.

However, there are also other important considerations to keep in mind when choosing a Nikon Z lens for astrophotography, and they in turn cannot be considered in total isolation from maximum aperture.

Read on to learn what these factors are and how they affect the apertures you can get away with using when photographing the night sky.

Sharpness

In effect, astrophotography involves photographing tiny pinpricks of light. The sharper and better defined those pinpricks are, the prettier they tend to look. Clearly then, lens sharpness is extremely important to the astrophotographer.

But when we say that a lens is sharp, this can actually mean a variety of different things.

Most lenses tend to be fairly sharp at the center of the image, at least when used at medium apertures; indeed, if a lens can’t manage this basic feat, it’s unlikely that anyone will buy it.

Trickier to find are lenses that are not only sharp in the center of the frame, but also at the edges.

Rarer still are those lenses that are sharp from edge to edge even when used at their widest aperture.

As you will take most of your night sky photographs at the lens’s widest aperture setting, and will want to capture sharply defined detail across the entire image, obviously it’s this last kind of lens that you need for doing astrophotography; sharp across the frame, even at its widest aperture.

This is the holy grail of astrophotography lenses.

Coma

Designing camera lenses is a challenging job. Lenses contain numerous pieces of precision glass that must be perfectly aligned in such a way as to capture and focus light with as few reflections, optical errors, and areas of uneven illumination as possible.

Some optical faults are almost inevitable and, while perhaps noticeable, will make little practical difference to the performance of a lens (a degree of flare, for example, is to be expected when shooting into the light).

Other optical defects will be totally undetectable under most common shooting circumstances (e.g. in the middle of the day, under bright sunshine), but will only become apparent when the lens is used in a particular way.

Coma is one such error. It’s fairly common, but isn’t a problem when using a lens in the way that 95% of photographers will use it. Unfortunately, astrophotographers don’t fall within that 95%.

But what is coma?

Comatic aberration is a kind of optical imperfection, a misalignment caused when rays of light entering a lens don’t refocus to a perfect point.

It’s most noticeable when photographing small points of light – such as stars – and will be visible as a kind of flare or trail behind the point of light. In effect this will make the star look like a shooting star or a comet (hence the name “coma”).

Coma affects off-axis light, meaning that it tends to be more noticeable the further you move away from the center of the image.

It also tends to be more evident when shooting at wider apertures, and may clear up once the lens is stopped down by a stop or two.

Unfortunately though, this is rarely an option that is open to the serious astrophotographer.

If you’ve followed the 500 Rule (see above) to determine the best shutter speed for your camera/lens/subject, and yet still notice what look like star trails in your photos of the night sky, this may in fact be coma.

Coma can be caused by an inherent fault in the design of a lens. I.e. the lens is just made that way, so there’s nothing you can do about it other than buying a different model lens..

Alternatively, a particular lens may display coma due to a manufacturing error.

In which case you should send the lens back to the manufacturer and demand a new, coma-free, one.

In theory, Nikon Z lenses are ideal for astrophotography, in that they are not only extremely sharp, but also tend to be very much free of comatic aberration.

Unfortunately, though, the Nikkor S line suffers from one major defect that will likely deter most astrophotographers.

We’ll look at this problem in the next section.

Focusing

Nikon Z-mount lenses generally feature great autofocus. Unfortunately, as autofocus doesn’t easily permit precise focusing on tiny objects positioned at infinity (i.e. stars), it is of little use to astrophotographers.

Of course, Nikkor S lenses also offer manual operation, don’t they?

Kind of.

While it’s true that S lenses come with a manual focus ring, this is actually what is known as “focus-by-wire;” a system that doesn’t provide genuine manual (i.e. mechanical) control of the lens elements.

Instead, turning the focus ring sends an electronic signal to the lens motor, which moves the elements for you.

Effectively this is just autofocus controlled by a different means.

And sadly the difficulty of making minor, precise adjustments to focus remains exactly the same as with regular autofocus.

To be clear, it’s not entirely impossible to focus sharply on stars using AF. It just involves a lot of extra hassle.

Unfortunately though, the Nikon Z lenses have another problem that makes them even less appropriate for astrophotography.

Namely, once you do find the right focus point, you better pray that your camera battery doesn’t run out, or that you don’t need to turn your camera off for any other reason.

Because if you do, you’ll only have to start all over again, as in the meantime the camera will have reset focus for you.

*** 2021 update: This is no longer an issue with the latest firmware update on Nikon Z cameras, make sure to update to the latest firmware to avoid this de-focusing problem! ***

In short, the ideal astrophotography lens is a truly manual focus lens.

And with the exception of the very expensive Noct 58mm – which is in any case unsuitable for astrophotography due to its longer focal length (see below) – Nikon Z-mount lenses do not currently offer this capability.

Focal Length

If you’ve ever used a telephoto lens handheld, you’ll have discovered that a longer focal length lens is harder to hold steady than a wide-angle lens; increasing the risk of camera shake.

It’s kind of similar with astrophotography.

Only here you’ll be using a tripod, so it’s not shaky hands you need to worry about, but instead star trails caused by the movement of the earth. And this movement will be more noticeable the longer the focal length of lens.

As a general rule, when using a full frame camera you should stick with lenses that are 40mm or wider.

This rule becomes 24mm or wider when using an APS-C sensor camera.

While it is possible to use longer focal length lenses than this to photograph the night sky, doing so will require the use of a “tracker”; an electronic rig that moves the camera to compensate for the movement of the Earth.

The only drawback to this solution is that any landscape features that you might want to include in the foreground of your shot will be blurred by the movement of the camera.

Meaning that a tracker is only really appropriate when photographing just the sky and nothing else.

In short, stick to wider lenses, and star trails will be much less noticeable. Simple.

Primes vs Zooms

As ever, prime lenses tend to have the upper hand over zooms when it comes to image sharpness.

Zooms are complicated pieces of optical engineering, and so it’s hardly surprising that manufacturers can’t always maintain the same degree of precision over the entire zoom range.

For some genres of photography, sharpness is only really a secondary consideration.

But as mentioned above, for astrophotography it’s almost everything.

As a general rule then, prime lenses are probably the first place you should begin your hunt for an astrophotography lens.

But it’s important to keep in mind that this piece of advice is only a guide, not a hard and fast rule. Some prime lenses perform relatively poorly on sharpness, whereas some zooms excel. As they say, the proof of the pudding is in the eating. And there’s absolutely no reason not to go with a zoom if you identify one that performs well in this area and fits your needs on all other fronts too.

As case in point, Tamron’s 15-30mm zoom (above) is undoubtedly one of the best Nikon Z lenses for astrophotography out there right now – of any kind. In part this is precisely because it is so exceptionally sharp, despite being a zoom.

Lens Mount

Although in itself the type of lens mount you use for astrophotography will make no practical difference to your photos, the fact is that the majority of the most useful lenses for astrophotography are simply not available in native form for the Nikon Z-mount system.

Given that the Nikkor S line of lenses are generally excellent, this may come as something of a surprise to learn.

And hopefully Nikon will eventually resolve this problem by adding a few more true manual focus lenses to the range. But for now the problems caused by Nikon’s use of the focus-by-wire system far outweigh any advantages that Z-mount lenses may otherwise offer the astrophotographer.

In short, the best Nikon Z lenses for astrophotography are mostly not Nikon Z lenses at all.

This being the case, unless you are willing to put up with the fiddly focusing and frequent missed shots caused by focus-by-wire operation, you will likely want to make use of third-party lenses such as those listed above.

This invariably requires the use of an adapter; do not expect a Nikon F-mount lens, such as the ones from Samyang, Tamron, and Sigma that we’ve recommended here, to work on your Z6 or Z7 right out of the box.

The good news is that Nikon’s FTZ adapter works very well and doesn’t result in any compromise in the performance of these lenses.

Nonetheless, this is an extra expense that you will need to budget for when putting together your Nikon Z series astrophotography kit.

Final Thoughts

Despite the generally exceptional quality of Nikon’s native Z-mount lenses, choosing a Nikon Z lens for astrophotography is a surprisingly difficult affair.

Or rather, there are several fantastic options available for astrophotography, it’s just that they tend not to come from Nikon at all, but instead from third-party manufacturers.

Do you have experience of shooting astrophotography with Nikon’s S-series lenses? Have you been satisfied with the results? How have you found focusing? We would love to hear your tips and opinions in the comments section below.

23 thoughts on “Top 6 Best Nikon Z Lenses for Astrophotography”

Hi! very interesting article. Because of it I decided not to buy the 14-30mm but to get a sigma art 14-24mm instead.

Cheers from Peru.

The sigma Art is a truly great lens 🙂 glad you liked the article!

Loved this article. I was about to purchase the nikon Z 20mm lens but tried to use my z lens at night. Its hopeless for repeatable accuracy except now a firmware update addresses maintaining focus if the camera is turned off for some reason.

Not sure which I will purchase but it will be an informed choice now.

I’ve seen you tube videos but this article reflects a well rounded review with all the positive and negatives of the more popular “astro” lenses. Thank you 🙂

🙏🏻 Thanks! I’m Glad you liked the article 🙂

astrophotography needs van telescope and utilities no ?

Not really! You’d be suprised what you can do with a simple tripod and the right settings. A Tripod is a must though, or any way to ensure your camera is completely still.

I have not experienced the problem you seem to have with the Z mount lenses manual focusing. I have taken astrophotos with my 35mm S, 24-70mm S and 85mm S lenses on my Nikon Z6 and have been able to achieve very good and precise focus in manual mode while zooming to 100% in the electronic viewfinder.

I got a Sigma 18-35 1.8 mounted on a Nikon d7000 (APS-C). I absolutely love that lens. Unfortunately, my D7000 does not allow me to take asto photos at high ISO. So the question is: should I upgrade to full frame or not. I’em reluctant, because of my Sigma 18-35. But perhaps on a Z50 or a D7500 I should get better results…

Hi Xavier! It depends what you shoot, but mostly full frame is a step up. For wide angle, landscape astrophotography, a full frame camera is going to get better results in general. Higher low light sensitivity and better noise management on full frame sensors will get you get cleaner, brighter images.

If you intend to shoot very wide landscapes at night like a Milky Way or aurora, the more narrow field of view means you won’t be able to expose your images for as much time as with a full frame on equivalent lenses (that is the key point, equivalent lenses) This can always be fixed with a shorter focal length lens though.

Well, what’s the use of ibis when taking astrophotography stills. I always put it off and use a tripod

Indeed, IBIS is better set to OFF for astrophotography 👍🏻

Sigma 14mm with FTZ adapter does not work well, the image at the edges is much worse than in the F system, so this lens cannot be recommended for the Z system. In my tests, all wide-angle lenses with an adapter perform worse, even Nikon 14-24mm.

Hi ,

May I suggest you Have a look at the new tamron 35mm 1.4 sp . very impressive even in the company of the 14mm art and 24mm 1.4 Samyang . I’ve been shooting mine on the Z6 with great results when the milkyway core is low .

The Nikon 50mm s is also ok but needs to be manually focused like you say whenever camera is turned off .

The Z6 is great for being able to pick up the body mount a lens and hand held focus on a star by zooming in evf before mounting on the tripod which saves so much time recompiling when you are juggling multiple lenses and focal lengths .

I find focusing the 14mm art best using a star in very corner of frame Until coma Shrinks away . It is very critical on focus or coma will grow quickly . It is hard to do as accurate focus in centre of frame To minimise the coma .

Cheers Rob

Hi Rudy, Very nice article. Loved it.

I have a question for you. I own Nikon z50 and I am really interested in doing sky Photography. I am planning to buy Rokinon MF 14mm f2.8 designed for Z mount. Will it be a good choice for it? I know it is a full frame lens but what things are to be considered ? I appreciate your help in advance. Thank you.

The Samyang / Rokinon 14mm f2.4 is a much better lens. It all depends on your tolerance levels, but the 14mm f2.8 is unfortunately infamous for quality control issues, with one or several corners being less sharp, wavy lines (mustache distortion)… You may get a good example or a lemon, which is why I did not included it in this list. If you still want to get it, make sure you can try several examples or you are able to send it back if needed 🙂

I’m interested whether you have tried the Samyang / Rokinon 14mm f2.4 SP with an FTZ. I chose it because it supports AE, and sends EXIF lens and exposure information to the camera body for recording in the image. I use it for exposure bracketed panoramas shooting so this was an important characteristic for me, but I recently bought one of these, and had to send it back because the the Z7 + FTZ couldn’t lock on to the EXIF information and the aperture value seen by the Z7 fluctuated all over the place. Luckily the store I bought it from had a mint condition Sigma 1.8 14mm Art at a similar price, & I’m very pleased with the result. With its USB dock, I’m a bit more confident the Sigma will remain compatible with newer cameras.

I bought the Sigma 14-24mm F2.8 art and the Nikon Z 20mm F1.8 lenses to try for astrophotography. Milky way is not in season anymore so I cant try it for those. However, the Sigma lens works well at night, but is so heavy and big that it is not practical to carry it around. You have to use the FTZ adaptor. The big pain is that the FTZ adaptor can not be attached to the camera after it is on a tripod. You have to attach the lens and adaptor before its on the tripod. The Nikon Z20mm F1.8 is a nice lens and seems OK to focus at night. But it will not capture the whole milky way like a 16mm or 16mm would. So I might return that too. The Nikon 14-24mm Z lens is $2,400 and very expensive to just use at night. You cant put a normal 77mm filter on it for daytime polarizer use, so its not practical for daytime like for waterfalls.

I may consider the Laowa 15mm lens for Nikon Z, but not sure about the focusing on that.

Hi, thanks for this article, I have a Nikon Z50, it seems even harder to choose a lens for this camera than the full frame Nikon Z mounts. I have the two Nikon kit lenses.

I’m drawn to the Tamron-15-30mm f 2.8 G2 because it seems more versatile and has image stabilisation, but as it’s slower than some other choices here not too sure how that will go with my Z50.

Then there is the Rokinon 14mm f/2.4 which seems great for Astro photography which is my primary interest here of course.

Do you have any specific recommendations for the Nikon Z50 in this area of photography? Thank you.

Hi , I have Nikon Z50 as well, have you finally tested out what lens is perfect for astrophotography with Z50? Thanks

Good article. One correction – the issue with the Nikon lens needing to be refocused after turning off the power was resolved with a firmware update. That’s no longer an issue.

Thanks for picking up on that! I updated the article

I have acquired the IRIX 11mm f4 Firefly and used it on my Nikon D810 for night sky photography with good results at 2200+ ISO and f4. I have ordered a Z9 with FTZ II and recently acquired the Z14-30mm f4 lens. What are your thoughts on using the IRIX 11mm f4 with theZ9/FTZ II combination? I would like to image the erupting Kilauea volcano and the night sky.

What are your thoughts on the Nikon Z 28mm (SE) for astrophotography? Thanks!